Using ideas from ‘Humble Inquiry’ to ask instead of tell

The importance of staying curious and asking questions in building positive and psychologically safe relationships: key takeaways from the book ‘Humble Inquiry’.

Overview

In this article we look at how the simple acts of showing humility and being genuinely curious, and of asking good questions and listening carefully to people’s answers, can help to create psychological safety and build positive relationships with our colleagues and across our organizations.

Introduction

It was only about a year ago that I ‘discovered’ Edgar Schein, having been introduced to some of his work when I was doing a postgrad course on change management with the University of Glasgow, through Futurelearn. Since then I’ve learned that not only is he regarded as one of the leading experts in the field of organizational culture and development, but he was also amongst the first people to develop and write about the idea of psychological safety. I’ve also been busily trying to put a (very) small dent in the many books that he’s written that suddenly made their way onto my ‘Books to Read’ list and ‘Humble Inquiry: The Gentle Art Of Asking Instead Of Telling’ is one of these.

‘Humble Inquiry: The Gentle Art of Asking Instead Of Telling’

This is a short book - even the revised and expanded second edition is only 130 or so pages - but it makes for compelling reading. It is part of the ‘Humble Leadership’ series which includes titles on leadership, consulting and helping; the second edition is co-authored by his son Peter Schein.

The book begins by exploring the difference between telling and asking, and describing what the authors call the ‘humble inquiry attitude’. This attitude is somewhere between science and art: fostering a sense of curiosity and interest, learning how to ask the right kind of questions, and also developing an acute sense of self and situational awareness.

It then moves on to consider our (Western) prevailing culture of ‘Do and Tell’, of how we value doing and telling over asking, listening, and taking the time to build positive relationships. Schein presents a model of Levels of Relationship: Level -1 is domination and abusive; Level 1 is transactional and role based; Level 2 is a more personal relationship based on openness and trust and getting to know each other; Level 3 is close friendship or love. He argues that to succeed in our VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous) world of today, we need Level 2 relationships. We need to invest in these positive Level 2 relationships so that people feel psychologically safe and able to ask questions, be vulnerable, be open, and take risks.

In the final few chapters, attention turns to what is really going on inside a conversation, what is going on inside our heads when we have a conversation, and how we can go about learning the attitude of humble inquiry ourselves. Schein introduces two frameworks to help us understand these processes: the Johari Window and ORJI cycle (observation, judgement, reaction, intervention) and also gives some practical suggestions for getting started.

There are no case studies as such, but scattered throughout the book are many short examples of conversations that Ed Schein has had in various situations over the years - some personal, others from his work. These range from conversations with CEOs about organizational change and succession planning, to the chance encounter with a stranger that Schein says was the prompt for writing this book. These examples help to illustrate the principles and practice of humble inquiry in a real-world context, and also make the book much more interesting and personal.

Each short chapter concludes with a Reader Exercise which poses some questions for the reader to think about and consider in their own context. At the end of the book, there is also a discussion guide with 8 further exercises (one per chapter) and 12 ‘mini case-studies’ to further illustrate how Humble Inquiry works in practice.

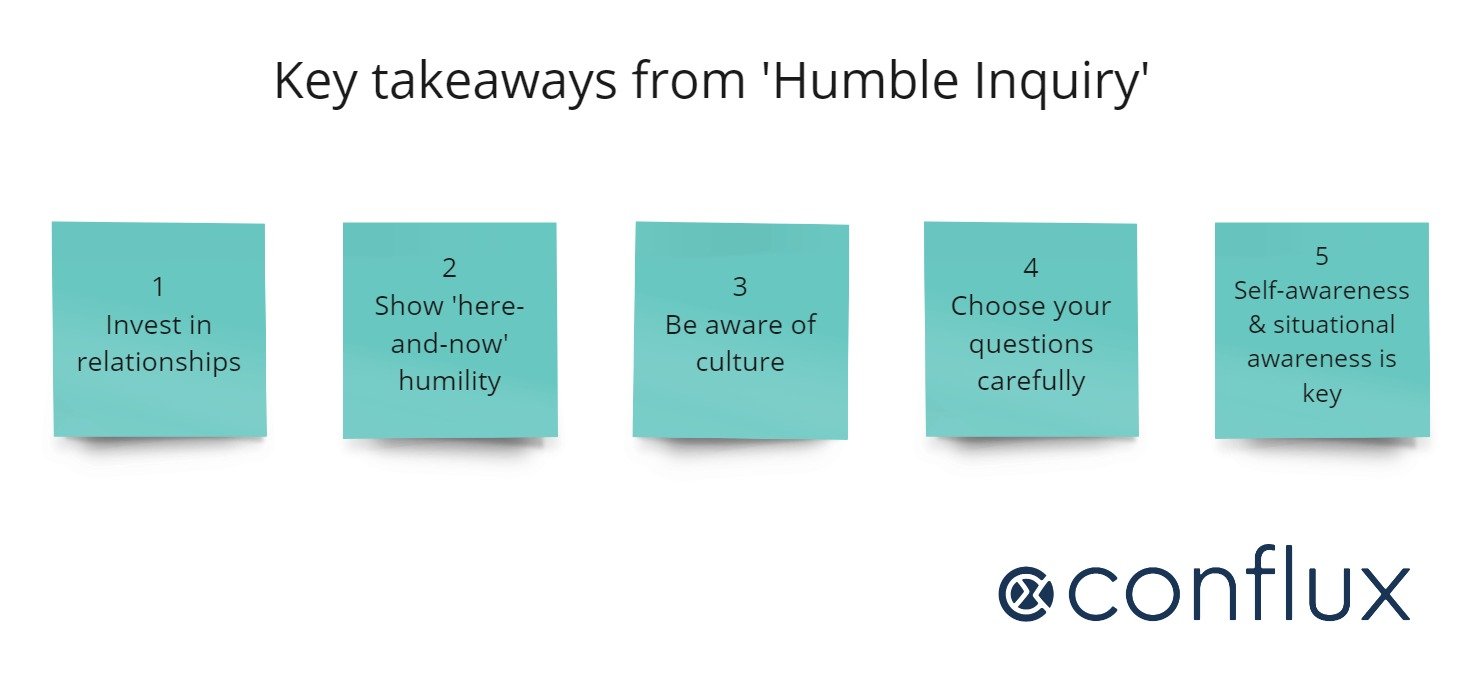

Key Takeaways from ‘Humble Inquiry’

I have a number of key takeaways from the book ‘Humble Inquiry’; crucially, that even the most senior leader in an organization does not have all the answers or knowledge, is dependent on others, and needs to (humbly) ask for help to complete tasks and achieve goals.

1 - Invest in relationships

Our world is becoming increasingly complex and we are increasingly interdependent on others to successfully accomplish our tasks and goals. Leaders no longer have the necessary knowledge or experience to be able to make all the decisions in any situation (see ‘Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement For a Complex World’), but must rely on others who do have that knowledge and experience.

To make it possible for those who are lower down in the organizational hierarchy to feel psychologically safe to speak up when the situation demands that they do, or when asked to do so directly, we need to create good relationships between people - relationships that are built on openness and trust. Schein’s argument is that ‘humble inquiry’ is the method by which such relationships are forged. These relationships need to be created before they’re needed, we need to invest in them upfront so that they are ready when the situation arises.

2 - Show ‘here-and-now humility’

Schein’s idea of ‘here and now humility’ is that those of higher status or rank need to be comfortable with admitting that they don’t have all the answers, or all the information needed to make a decision. Having and demonstrating this humility is the humble part of humble inquiry.

One example is that of a surgeon, who often would be seen as the highest-status person in an operating theatre, but who cannot perform an operation without the assistance of the nurses, anaesthesiologist, and technician.

Dr Amy Edmondson also talks about the need for humility in her book ‘The Fearless Organization’ (read our review of the Fearless Organization here) where she cites the work of Ed Schein, although she calls it ‘situational humility’ and says that in our fast-moving and ever-changing world such humility is simply realism.

3 - Be aware of culture

Culture plays a number of roles in how we ask and answer questions. Firstly, we who live in Western cultures need to be aware of our prevailing (Western) culture of ‘do and tell’. We prefer to tell instead of asking - we like to give our opinions, give advice, get to the point; we value people who have a ‘bias to action’ and we all know that a successful meeting is one that concludes with everyone taking away some action points to complete.

In our increasingly connected and multicultural world, we also need to be aware of other cultures and consider how cultural norms - in particular those around the status of individuals - can colour a person’s view of how and when it is appropriate to ask questions or speak up.

One other way in which culture can affect how we ask and answer questions is that it creates scripts. Some questions which may sound open aren’t really so in practice because they have an expected and scripted response: “Hi, how are you doing?” will inevitably elicit a reply of “Yeah, good thanks - how are you?” no matter how that person might really be feeling.

4 - Choose your questions carefully

Humble inquiry questions are open and don’t try to control the conversation either in content or context. That may sound simple, but it’s not as easy as that in practice! Schein describes three types of question: diagnostic, confrontative, and process-oriented, and four different ways that they can be used: sense-making, feelings, action-oriented, and systemic.

Diagnostic inquiry is when you become interested in a particular thing that the other person is telling you and you focus on that and try to steer the conversation in that direction. By doing this you are influencing the conversation for your own purpose.

Confrontative inquiry is where you insert your own ideas in the form of a question; it is related to something that you are thinking about or want information on.

Process-oriented inquiry is where it gets a bit meta and is where we ask questions which shift the conversation to the conversation itself when it feels that it’s somehow going wrong. Shein says that these types of questions can be considered humble inquiry depending on whether or not the intention in asking is to help build the relationship.

5 - Self-awareness and situational-awareness is key

The art and attitude of humble inquiry is something that we need to work at and practice. We need to consciously seek to build positive relationships with our colleagues, we need to be aware of how our cultural norms affect our behaviour, and we need to learn how to ask better questions and listen more carefully to the answers.

Humble Inquiry in practice at Conflux

At Conflux we work with customers in multiple sectors helping them to optimize for fast flow by running what we call ‘guided workshops’ and facilitating conversations amongst leaders and sometimes across the wider organisation to help surface questions, new perspectives, and opportunities, and to enable people to have better conversations and come to a shared understanding. Many of the ideas of humble inquiry - ignoring status and demonstrating ‘here and now humility’, asking open questions, showing genuine curiosity and listening carefully to what’s said, investing time in building positive relationships - are embodied in these workshops and the conversations that take place.

Summary

To succeed and thrive in today’s complex, fast-moving, and interconnected world we need to create positive relationships with those we work with - relationships that are based on openness and trust and where we feel psychologically safe.

In ‘Humble Inquiry’, Edgar Schein argues that the way we create those relationships is through the practice of ‘humble inquiry’ where we are genuinely curious and don’t assume that we already know all the answers, where we ask open questions and listen carefully to the answers.